By Hedy Korbee

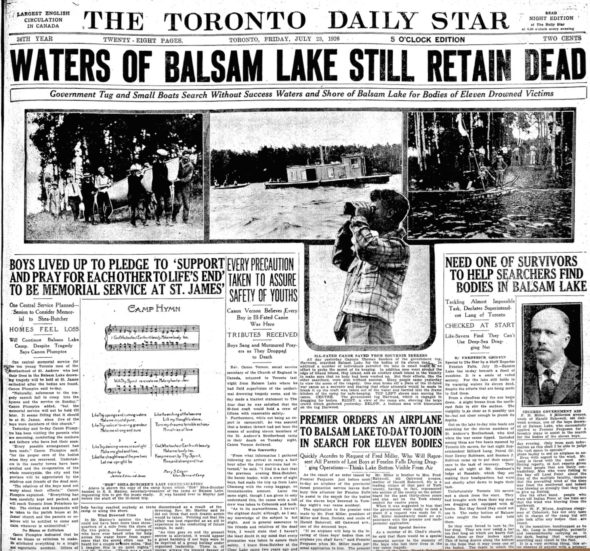

It was a tragedy that made headlines around the world.

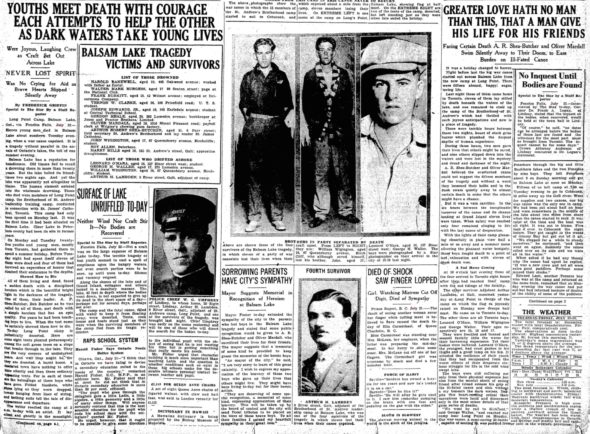

Ninety years ago today, on Aug. 3, 1926, a 16-year old Birch Cliff boy testified at an inquest about a horrific boating accident that killed 11 people, including his older brother.

William “Willie” Wigington,16, and his brother John,17, lived at 87 Queensbury Ave. and in the summer of 1926 they went to an Anglican Church leadership camp at Balsam Lake near the town of Kirkfield, Ontario.

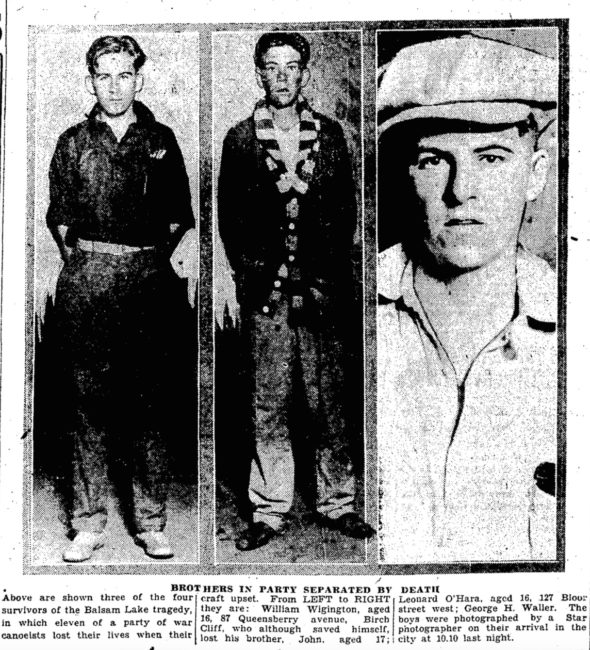

Upon arrival on July 20, the Wigington brothers were among 15 people who set off in a 30-foot war canoe to purchase supplies in the town of Coboconk.

Those on shore recalled that the canoe had a full crew. They had paddles at the ready and at the word “dip’ they “struck off and disappeared in the dusk.”

A mile or two from shore the war canoe capsized.

Initial reports of a sudden squall with heavy wind and waves were later discounted and questions were raised about the experience of the paddlers.

Birch Cliff’s Willie Wigington, who could barely swim, described what happened in the July 22 edition of The Toronto Daily Star:

“It was queer,” says Willie Wigington, “it started so suddenly and turned so slowly. We were all sort of balanced for a minute and then we were scrambling in the water. I swam back to the canoe and kept getting pushed and shoved by others but I got hold of the canoe at one end and hung on.”

When the canoe overturned the Wigington brothers and the other campers were directed by their leader and founder of the church group, Robert Shea-Butcher, to cling to the gunwales (the edges of the canoe) and try to paddle to shore.

There were seven people on each side of the canoe and Shea-Butcher hung on at the stern.

The water was cold. The canoe was freshly painted and slippery. The boys sang and prayed.

“They went to their death without a whimper”

“They went to their death without a whimper”

One of the first victims, Oliver Mardell, 18, of Mt. Pleasant Rd., died within an hour.

Survivors recounted that before he drowned Oliver swam around the canoe and dove underwater to lift the smaller boys by the ankles so they could hang on.

The Star reported that Oliver quietly swam away from the canoe when he saw it would not support everyone’s weight.

Sadly, Oliver met the same fate as his who father drowned in 1914 during the sinking of the Empress of Ireland in the St. Lawrence River.

A similar decision was made by Shea-Butcher, a war hero who could not swim.

Believing that he was delaying their progress to shore, survivors said he deliberately let go of the canoe to lighten the load in hope that the rest of the boys would live.

Another boy, Ray Allen, then tried to swim for shore to get help and drowned before he had gone 100 yards.

“All of them living and dead, faced a sudden death with a disciplined heroism which is the beautiful bright light in the darkness of the tragedy,” wrote legendary Toronto Star reporter Frederick Griffin in a style of prose common in that era. “[Shea-Butcher] met death with a simple heroism that has an epic quality. For years he had been teaching boys to live. When the test came he certainly showed them how to die.”

Arthur Lambden, an official with the church group and the only other adult in the canoe, described to The Star what happened next.

“The boys dropped off [the canoe] one by one as their strength failed them. “They went to their death without a whimper and to the last unselfishly trying to help the other fellow.”

And that’s also what happened to John Wigington, according to Willie’s interview with The Star.

“My brother John was at the far end from me,” says Willie, “and I could see him looking for me. He saw me and called out to me to hang on hard. I did. It seemed a long time, an hour or so. A boy beside me let go and I felt him slip down into the water. My head was turned away from my brother but at last I managed to turn again and look for him. I could not see him but I did not know certainly that he was gone until later when there were only four of us left.”

Only four people, including Willie Wigington, managed to hang on for six hours until the canoe landed ashore at Grand Island at about 2am. After a few hours rest they paddled back with only two oars and walked back to the camp, arriving mid-afternoon.

In an interview with The Star survivor George Waller attributed the drownings to the cold and exposure that made the campers’ hands numb.

“It was not,” said he, “that he water was so extremely cold but the wind which came up chilled us to the bone. Many had got rid of their shoes and trousers and felt the cold all the more. I fell off three times I was so weak, but I managed to get hold of the canoe again.”

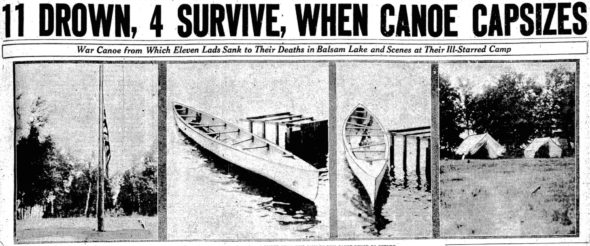

It took four days to recover the bodies, including that of Birch Cliff’s John Wigington.

A modest “English lad”

The Wigington family immigrated to Canada from England around 1912 and eventually moved to Queensbury Ave. at a time when there were very few houses in Birch Cliff.

The father was a plumber and there were five children, including John and Willie, who all attended Birch Cliff Public School.

Reporter Frederick Griffin was at Union Station when the four survivors returned to Toronto.

Reporter Frederick Griffin was at Union Station when the four survivors returned to Toronto.

He described Willie as an “English lad” who was “modesty itself” and whose story had to be dragged out of him.

“There were no dramatics, no excitement, no emotion. There was just a boy in a khaki shirt, collar unfastened, coat over his arm, cheeks burned with sun and fair hair curling crisply about a clever head, a boy who looked at one calmly out of bright blue eyes an spoke in the low steady tones of proper English reserve”, Griffin wrote.“He told his story, his pitiful story, a dozen times, always patiently, always courteously, almost impersonally. There was not hint from emotion or grief or even weariness.”

When Willie arrived at his house on Queensbury, his family wasn’t home because every summer they camped for two months at the beach at Highland Creek.

Neighbours went to fetch his mother and father and when they arrived The Star described Mrs. Wigington as being in a “state of collapse” and her husband dazed.

“Then Willie saw his mother and the sobs came. She clutched him frantically and he clung to her. He was her son snatched from death, her son doubly dear now and doubly precious. She was his mother, the mother for whose comforting arms he had ached during all those frightful hours of death, the mother who would see the horror she had pent up within his heart and memory,” Griffin wrote.

In an interview with The Star published July 23 Mrs. Wigington described her son John as a talented musician who played piano and had a voice of “exceptional purity”.

“He was a good boy, loving and upright,” grieved John’s mother to-day.” The are all good boys for that matter but John seemed just a little dearer than the rest. The Lord always seems to take the best of them.”

“I can bear it as long as his mother keeps up,” Mr. Wigington said to-day. “We have to remember the others, and I keep reminding myself that I am British, and that it is their ability to carry on in the face of things like this that has made the race. We might have lost Willie too.”

After the accident, Mr. Wigington travelled immediately to Balsam Lake to witness the search for John’s body and gave an interview to The Star.

“As soon as I saw that great expanse of water I knew it was hopeless,” he said. “I had thought that perhaps with so many islands the boy might have got ashore on one of them. But I knew that on so big a body of water as that no one could have a chance.”

“And when I examined the canoe I got a fresh idea of the terrible struggle those poor lads must have gone through. There was nothing to give them a grip on its smooth bottom…in the fresh paint were the marks of their poor little fingers. In one place there was a scratch two yards long; and you could see where they had sunk their nails in the wood in a desperate struggle to hold on to life.”

Inquest recommendation

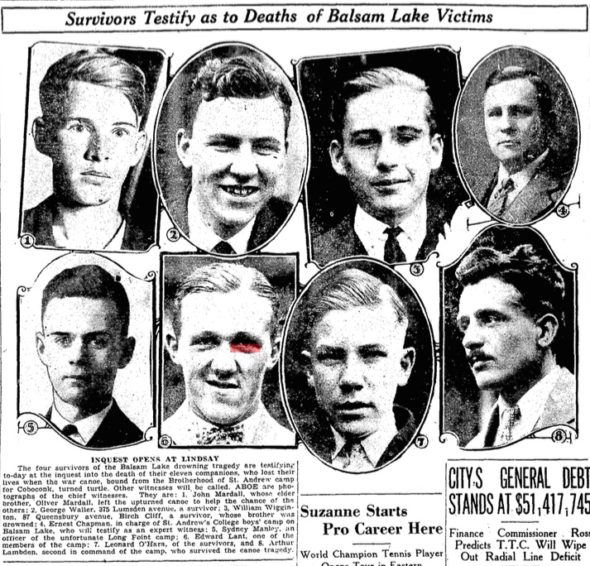

The coroner’s inquest was held on Aug. 3, 1926 in Lindsay with testimony from the four survivors including Willie.

The jury recommended that war canoes be prohibited at boys and girls camps.

In the Aug. 4 edition of The Star, General Manager Wyse of the Ontario Safety League noted that the Boy Scouts have a ban on war canoes and said: “The canoe is such a dangerous craft that the only safe thing is not to have anything to do with it.”

“The water accounts for more deaths in year than the automobile, yet there is a code of statutes that surrounds the automobile because people recognize it as a dangerous instrument. Nobody will quarrel with any regulation that would prohibit the canoe at summer camps altogether,” Wyse said.

Mrs. Wigington said she felt it was “the only verdict the jury could have brought in”.

“I also agree that war canoes should be abolished from such camps. Only those who have lost someone dear to them in this way can realize how we feel about it all – but my other children will never go in canoes again, I’m sure, and I do hope they will not go bathing either,” Wigington said.

Ontario’s Acting Attorney-General, W.H. Price was quoted as saying the province was unlikely to take drastic action, citing the popularity of canoe clubs in places such as Toronto and Hamilton.

He promised to refer the jury’s recommendation to Attorney-General William Nickel when he returned to work.

~~~~~

This is article is part of a community “Today in History” series commemorating the upcoming 100th anniversary celebration of Birch Cliff Public School taking place on Sept. 23/24, 2016. To see other articles click here: 1927, 1929, 1935, 1935, 1951, 1993, 1796, 1991, 1983, 1988, 1985, 1930, 1996.

I expect there wasn’t a requirement for life jackets, a sad story. It was interesting to read how news written in the past.

Not sure who reads this comment box, but I am wondering if any of the 4 people who survived the boating accident are still alive.

That’s a very good question! We just shot a movie in Toronto of this story! I hope someone is alive to see their memories of their friends.

I caught wind of this and was quite surprised that somebody else had picked up on this 90-year old story. How did you hear about it? When and how will your movie be released?

I would love to see this movie once it comes out! I believe that John William Wigington was my great-great grandfather. His son Bill was my grandma Diane’s father. My father lived in Toronto and I do have a few pictures. I found out about the Balsam lake tragedy while going through my family photos and finding a picture with words written about this on the back. I had no idea about any of this but it’s shocking to find this family history. If possible it would be great if you could contact me at alia.finley@outlook.com